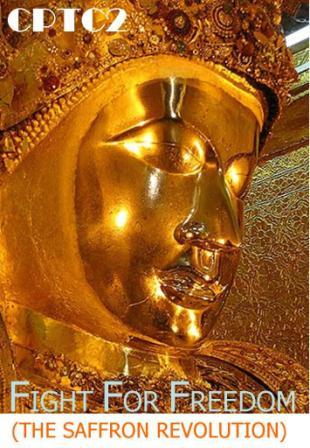

How to Save Burma's Future Generations?

By Yeni November 9, 2007

Wounds pass through the generations

The 88 generation never got a rest

The 96 generation never got a rest

Now, the 2007 generation has no rest

The wounds of the 88 generation should be healed

But the potential for the next generation has been destroyed

—Yaw Han Aung

A Burmese poet, Yaw Han Aung, wrote these words in his poem "Crushed Nation," after seeing the crackdown on the freedom uprising in September—literally led by young monks [See: http://yaw-han-aung.blogspot.com/].

Of course, we Burmese have grown up in a totalitarian system, and we are painfully conscious of how our country has lagged behind the rest of the world for decades.

That knowledge—and experience—is what's driven thousands of Burmese to sacrifice their lives—people shot on the streets, imprisoned and forced to flee the country—in the hope of creating a democratic, free and prosperous nation.

As a university student in 1988, my circle of friends had an acute awareness of the country's dire straits after the demonetization in September 1987, in which about 80 percent of the currency in circulation was lost.

We went to the streets calling for change. Unfortunately, many people lost their life, gunned down by soldiers, led by a junta that called freedom-loving people "destructive elements," puppets of the communists and the CIA.

In the current freedom demonstrations, which began on August 19, people again took to the streets calling for political and economic change.

Each new generation has witnessed the further deterioration of the country. According to the UN and other reliable institutions, Burma's public sector, especially health and education, ranks among the worst in the world. The estimated per capita GDP is less than half of that in Cambodia or Bangladesh. The cost to each new generation—in terms of aspirations and hope—is devastating.

Traditionally, the Burmese people have believed that society rests on three highly regarded institutions: "Students," "Monks" and "Soldiers." All three groups fought for Burma's independence from the British colonial power and the Japanese occupation. All three had a dream to build a new nation.

Unfortunately, the power of the military increased rapidly through its fighting various insurgencies—including the Communist Party of Burma and Karen and other armed ethnic separatist groups. But during those years after Burma gained its independence, the soldiers served under the command of a civilian government, headed by U Nu.

Ultimately, however, starting in 1962, led by the late dictator Gen Ne Win, the "Soldier" class betrayed the "Student" and "Monk" classes through coups, killings, imprisonments and torture. As the poem says, the potential of each new generation as been destroyed. The present regime, led by Snr-Gen Than Shwe, is just more of the same.

The Burmese understand that every country needs the "Soldier" class and an army to protect its own people—not to kill and oppress. There is a legitimate role for Burma's military as a national institution—but not as a corrupted, oppressive body. It is shameful for the "Soldier" class to continue to oppress each new generation of the Burmese people.

Ordinary Burmese remember the poignant words of the father of our country, the independence leader and the founder of the modern armed forces, Gen Aung San: “There are others who are not soldiers who have suffered and made all kinds of sacrifices for their country. You must change this notion that only the soldiers matter.”

For a better future, Burma needs two things: First, the Burmese people must never give up. Ordinary people—and students and monks— must work to ensure that future generations have a better life. Second, the "soldier" class must return to its roots as an honorable institution, guided by self-sacrifice, self-discipline and a dedication to serve the people.

Sunday, November 11, 2007

Posted by

CINDY

at

8:58 PM

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment